Tim Gilman-Sevcik at the farm, holding a line of Gowanus kelp in front of Red Hook Grain Terminal. Daniel Shailer

As the corporate clamor for carbon-capturing crops grows louder, a Brooklyn kelp farm tries to find the balance between building community and cashing in.

Daniel Shailer

When it comes to kelp, there are three types of people. Some don’t know what it is: Seaweed? An obscure species of fish? Some hate it—for it is, in fact, one of the most commonly found forms of seaweed, the clingy sludge determined to ruin a day at the beach.

But for others, it is a beautiful, hopeful fascination. Tim Gilman-Sevcik is one of those people. He works from a boat covered in seagull droppings, running on solar power and combusted manure. It moors at the mouth of New York’s most fetid waterway, the Gowanus Canal, in the shadow of a discontinued concrete storage yard and the graying, “magnificent mistake” that is Red Hook Grain Terminal. Gilman-Sevcik announces to visitors: “You’re surrounded by garbage!” The boat itself is garbage: a rusting barge no one else wanted, which Gilman-Sevcik has turned into a base of operations.

The water around it isn’t much better. After almost two centuries of industrial abuse, the Gowanus is absurdly polluted. From a toxic layer of sediment known as “black mayonnaise,” to its glossy, oil-slicked surface, the water contains typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis and—recent tests have revealed—gonorrhea. At first glance, the Gowanus is a place where marine life goes to die. A decade ago, a dolphin mistakenly swam in and washed ashore riddled with parasites and gastric ulcers; in 2007, a baby minke whale suffered the same fate, but not before locals could give it the nickname “Sludgie.”

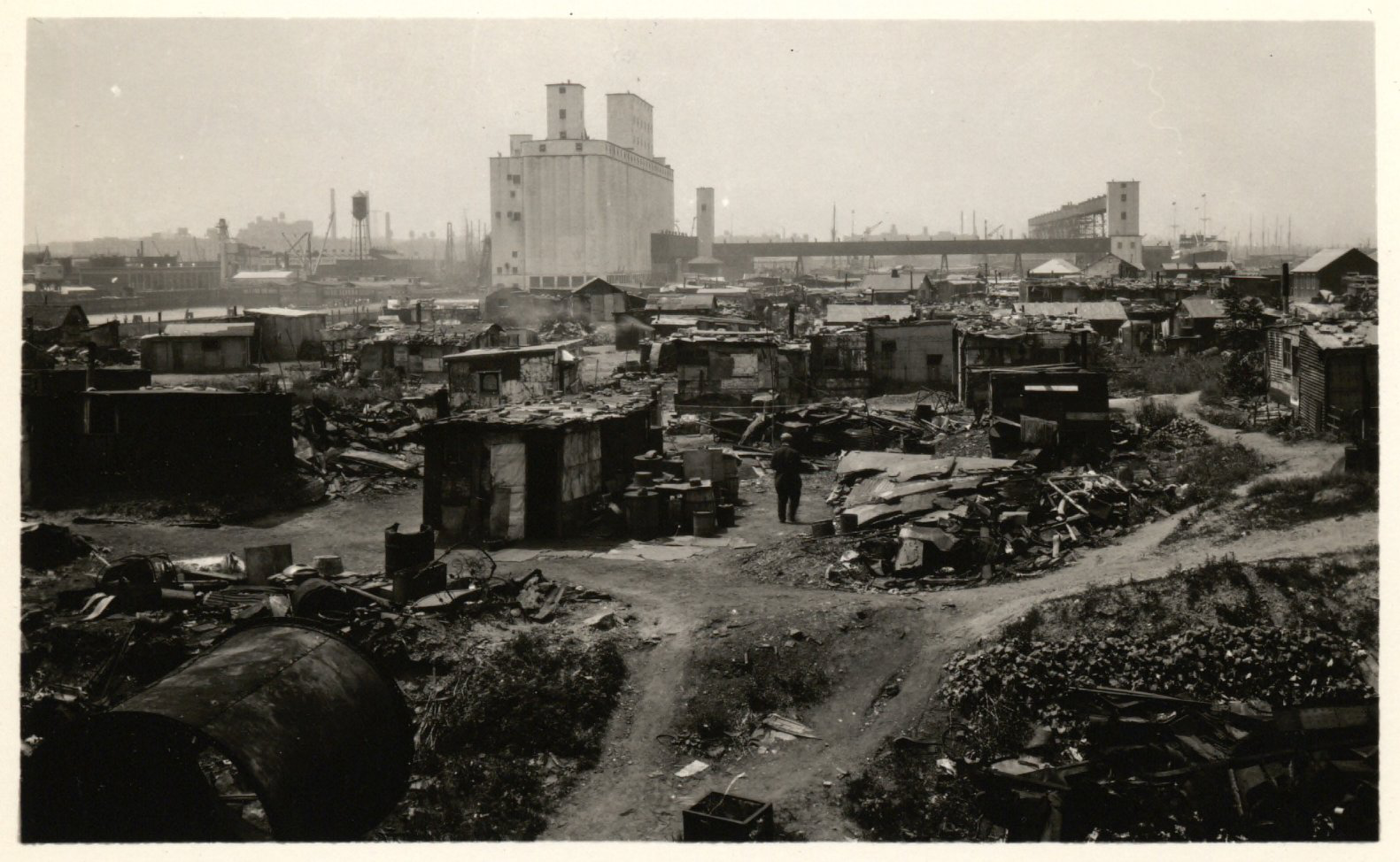

A “Hooverville” shanty town at the foot of the Grain Terminal in 1930. NYC Municipal Archives Collection

Opposite the Terminal, the Environmental Protection Agency has spent over a decade attempting to clean the Gowanus. Daniel Shailer

Which makes it all the more improbable that Gilman-Sevcik is now trying to farm here. “You wouldn’t think it, but this water is very much alive,” he said, one afternoon in January. “People think it’s so dirty, so polluted, there’s so much feces”—but that feces, pumped from Combined Sewage Overflow pipes untreated into the canal, provides the same nitrates found in fertilizer to whatever plants can survive.

From the barge, Gilman-Sevcik reached into the water to pull on a corded rope tied to a mossy block of cement. For someone handling a curdled chunk of the Gowanus’ black mayonnaise, he was surprisingly ginger. “You have to be careful disturbing it. This is someone’s house,” he said, pointing out sea squirts the size of a pinkie nail and even smaller shrimp, twitching against his orange rubber glove. “This is a little environment.”

Gilman-Sevcik is Executive Director of the RETI Center (which stands for Resilience, Education, Training, and Innovation), a small environmental justice nonprofit which runs training programs and models urban environmental adaptations to climate change. Through RETI, Gilman-Sevcik oversees community solar installations, science lessons at a local school, and a green jobs internship program. He also thrives here at one extreme edge of New York City. Flanked by industrial ugliness, Gilman-Sevcik imagines a future “BlueCity” stretching away from the barge across four and a half acres of water: what he calls “a living floating lab” for climate resiliency research.

But for now, Gilman-Sevcik is trying to grow some kelp. In December, he and his team embedded kelp seeds into six lines of rope, which they stretched across different parts of the water. They planted them at different dates and depths to experiment with temperature and light exposure. Initial indications are positive. The older kelp in the pen is already thick and heavy to pull out of the water. Out in a canoe for a “kelp check-up” one afternoon, a volunteer took calipers to a long line and measured an inch of growth from the week before. If it could survive until April, he said, when the water warms up, it will begin to really thrive; kelp can grow several feet per week once the water gets warm enough. But there were still dangers to contend with, from the lack of a strong current to the possibility that the Gowanus is just too dirty to sustain life.

Gilman-Sevcik came to RETI after his experience of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Floodwater swept Red Hook, where he and his wife have lived since 1998, like a river. Water surged through his basement and up the chimney, collapsing its supporting wall in a 21-foot “arc” up the house. It would be six years before Gilman-Sevcik, his wife, and children (then three and seven), could return to their home.

Not all his neighbors were so lucky. Insurance payouts and state grants were notoriously difficult to navigate. Gilman-Sevcik, then working at an ad agency, began advocating for the community: fighting insurance companies and helping fill out grants to the state’s Build It Back recovery fund. This is how he caught the attention of Gita Nandan, an architecture professor looking to start a non-profit modeling climate resilience in the city. She laid out her vision and, even though the group hardly existed, Gilman-Sevcik signed on.

“When I started there was zero operating budget and $500 in the bank,” Gilman-Sevcik said. His first responsibility was to find a grant to pay himself.

RETI became an official non-profit in 2016 and since then has grown with the help of government grants and private research investments. Now, from interns to experts, RETI is a team of two dozen, with a burgeoning corps of volunteers. Two years ago, the owner of a cement yard on the Gowanus leased them the barge for free. A year later, RETI started working on “floating gardens”—collecting thousands of old wine corks to plant marsh grasses on. The kelp farm is their first experiment underneath the water.

Farming in the Gowanus Canal still presents a fundamental paradox: anything grown there is so toxic not even animals can eat it. And legally, Gilman-Sevcik’s farm is in limbo. Because it doesn’t have a permit, it can’t be commercialized, or even technically called a “farm.” So Gilman-Sevcik will not only have to find a use for the kelp, he’ll have to be persuasive. If successful, the RETI farm could show that kelp grows in the most toxic water imaginable. At scale, it could set an example for the city’s next climate adaptation—its sludgiest yet.

Around the world, kelp is having A Moment. As the Paris Agreement forces governments to consider emissions taxes and subsidies for carbon markets, corporations are looking for ways to offset their own pollution and ease the growing pains of decarbonisation.

In the months since December, when the first crop of Gowanus kelp was seeded, Microsoft and Amazon have each sunk millions of dollars into researching the plant’s carbon capture potential. Amazon is betting on a 250-acre “commercial-scale seaweed farm” between wind turbines off Denmark. Microsoft will send kelp-seeded buoys from Maine and Iceland into the open ocean, to grow and eventually sink.

They join companies like Shopify and Stripe in trying out kelp, each investment stretching the plant’s slippery fronds further into the highest echelons of corporate climate policy. Even as kelp forests around the world succumb to warming oceans, kelp farming finds itself the darling of the nascent carbon offsetting industry.

Like any other plant, kelp absorbs carbon to photosynthesize light into energy. But it’s particularly effective because it grows fast (for some species, as much as two feet in a day), needs very little encouragement, and, where fronds are allowed to grow and die near the seabed, will gradually be covered in sand. The carbon that is sequestered in this way is effectively locked away for good: out of sight and out of the carbon cycle driving global warming.

In the past, the golden children of emissions offsetting have been reforesting programs or scientific techniques which artificially grab carbon from the atmosphere, known as Direct Air Capture (DAC). The jury is out on the latter: the Department of Energy (DOE) invested $3.5 billion in DAC this January; the same month, research showed that the best DAC techniques currently available are so power intensive they would emit 3.5 tons of carbon for every ton captured.

Reforestation—despite the marketing success of corporate tree planting—is even less credible at scale. Newly planted trees can’t absorb enough carbon to offset industrial emissions quickly enough, and when they die, each tree begins releasing some of its carbon back into the atmosphere as it decomposes. With so many demands for land already, there just isn’t enough space. Here kelp plays a trump card, presenting itself across miles of coastline and open ocean.

Some scientists think kelp has even more to offer us. You can harvest it to replace more carbon-intensive materials: as an ingredient in cement, for example, or processed into a plastic alternative. While it grows, kelp absorbs pollutants like agricultural runoff and sewage, leaving the water around it cleaner. Some scientists call kelp the “swiss army knife” of climate solutions.

Today, the U.S.’ largest natural kelp forests are off the West Coast, where 21 different species grow together in swathes across thousands of acres. But overfishing and warming water both threaten to destroy them. Between 2014 and 2019, 93% of California’s kelp forests died, after an infamous “blob” of relatively warm water drifted ashore. What survived the warmer water was promptly eaten by purple sea urchins and sunflower starfish, less sunnily known as “the wolf of the subtidal oceans,” by marine biologists. Both would normally be eaten by their own predators were those not hunted to endangerment already.

And without kelp, everything dies. Once urchins have grazed kelp forests to underwater barrens, they become morose and begin to digest their own reproductive organs until all that remains of one of the planet’s most vibrantly interconnected eco-systems is a bristly purple mat of “zombie” urchins.

Around the world, warming water and fragmented food chains are wreaking havoc on kelp forests: from Australia to South Africa, Nova Scotia to Chile. Where it has survived, kelp has, for the most part, been monetized.

Japan’s oldest codified laws made it clear in 701 A.D. that kelp was as good as

cash when it came to paying tax. Now Japan and the Asia-Pacific region have the largest seaweed industry in the world, grown and farmed for food so successfully that the World Bank suggested it as a scalable solution to world hunger. Because it makes up the largest commercial market for wild seaweed (processed for a binding agent used in toothpaste and cosmetics), Chile leads the world in researching sustainable seaweed reproduction.

Now North America is waking up to kelp’s potential as a cash crop. The earliest modern farm, proposed by Dr. Howard Wilcox in 1972, drew funding from the Navy, what later became the Department of Energy, and the American Gas Association, among others. The plan was markedly similar to corporate kelp today: huge, free-floating farms drifting across the Atlantic and harvested in the summer for biofuel.

But by the end of the 1970s, gas was deregulated, oil de-embargoed and funding dried up, so the Ocean Food and Energy Farm dried up too. Dr. Wilcox’s son, Brian, now runs Marine BioEnergy—an enormous constellation of drifting mechanical kelp farms operated by satellite and staffed by submarine drones. The Department of Energy granted the project $2 million in 2016.

Anchored off Chile two centuries ago, Charles Darwin saw a kelp forest for the first time. He immediately recognized it as an overflowing sanctuary of life. “If in any county a forest was destroyed,” he wrote in The Beagle’s diary, “I do not believe nearly so many species of animal would perish as would here, from the destruction of the kelp.”

At the city’s edge, RETI Center’s kelp farm. Daniel Shailer

One recent Friday afternoon, Gilman-Sevcik received an exciting delivery: hundreds of corks, packed into about a dozen boxes filling up an old, cork-beige Toyota Corolla. Some of the corks had faded red lips straight from a local wine bar; others were taken from compost, covered in what one volunteer described as a pleasant “patina.”

Corks biodegrade slowly, so Gilman-Sevcik collects them. In number, they will give buoyancy to small plantbeds shaped like geometric lilies and floated off the barge. Like growing kelp in the Gowanus’s industrial filth, collecting 100,000 corks from the biggest city in the planet’s most polluting country—all to create biophilic, “small salt marsh archipelagos”—requires a degree of hope bordering on whimsical.

“I feel like doom and gloom is so, like, 2015, you know?” Gilman-Sevcik said in

the car afterwards. “It’s very passé. We’re all reckless optimists.” A volunteer disagreed, and Gilman-Sevcik paused. Is optimism justified? “I think that it’s a more productive attitude. Things have started to change,” he said. “And it’s going to be bad, but we can make it less bad.”

To Gilman-Sevcik, a father of two, there are still degrees of hope worth articulating. “We’re screwed. Yeah. But how screwed?”

Back at the farm, the next kelp checkup one Sunday afternoon painted a mixed picture. One line was heavy to lift and dripping for as long as it was suspended out of the water. But on another, each frond was just an inch long and mostly detached from the rope. A third was completely dead, leaving in its wake a muddy cloud of slipgut: algae which suffocates seaweeds and which aquaculturists ruefully compare to snot. The line, volunteers agreed, was hung too shallow.

Volunteers Justin and Braley on a kelp checkup. Daniel Shailer

Even with lines strung perfectly across all four and a half acres, could Gowanus kelp make a difference? Another farm growing the same species in Puget Sound found that with half the space they could produce around 20 tons of kelp. Growing at the rate of that farm, Gowanus kelp could, at peak growth, remove just over 850 kg of carbon in a year: the equivalent CO2 that a typical car emits in eight months.

But kelp may have other uses that could augment its carbon-fighting potential. As Gilman Sevcik and the volunteers loaded back into a car now capaciously empty of corks, they drove north past the dregs of Red Hook’s industry: a refrigerator coolant company, a warehouse for iced tea, and Quadrozzi Concrete trucks. Quadrozzi is the reason RETI’s farm can exist in the Gowanus. Infamous for alleged mob ties and legal battles with the city, the family closed the cement transport yard here and now rents the water to Gilman-Sevcik’s farm for free. And though Quadrozzi is now out of the cement business, Gilman-Sevcik and RETI are hoping they can get into it.

Manufacturing cement creates double the carbon off all plane travel—8% of the world’s total CO2 emissions. But dried and milled, even toxic Gowanus kelp can make up one fifth of a batch of cement. If Gilman-Sevcik’s farm matches the comparable one in Puget Sound, its maximum yield could help make nearly 200 tons of “sea-cement.” Gowanus kelp still won’t fix global warming, but suddenly it has the potential to offset over a dozen times more carbon than if it were just grown and sequestered under the seabed.

For Gilman-Sevcik, the value of RETI’s kelp farm isn’t just in carbon capture or water quality, but community involvement. “We’re always doing so many things,” he said from the backseat, “but all of our things are very small, you know? We try something, model it, hope that other people do it, try to make it grow, try to give individuals rather than institutions the opportunity to be involved, feel responsible.”

Together, he said, people might encourage their friends “to vote this way and raise your children this way.” Gilman-Sevcik explained all this while taking a call from the school, giving directions to the volunteer driving, and texting his wife to explain why he was running late. After a quick discussion of printing flyers, delivering corks, the next round of internships, and community solar training, he left to pick up his kids.

“Thank you guys very, very much,” he said through the car window. “That’s an amazing quantity of corks we’ve got.”

As he treads the line between scale and impact, between local engagement and the kind of performative advocacy that Brooklyn has become infamous for, Gilman-Sevcik has drawn support, frustration, and some controversy. One on hand, another project in the city has accused Gilman-Sevcik of overstating the potential of Gowanus kelp. Meanwhile, the farm’s own advisor, Roger Bason, sees more opportunities to monetize.

Bason wasn’t always a kelp consultant. First he wrote environmental policy for McGovern’s presidential campaign in the 1970s. Then he traveled the world patenting plans for the U.S.’ first tidal energy project. In between, he taught martial arts, lectured at Columbia, and acted in the all-star Western Silverado (1985). It is clear from talking to him—and from his four-page résumé—that Bason lived many lives before becoming an advisor to RETI’s Brooklyn farm, and starting his own international kelp business.

The key to making things happen at scale, he said, is “money, money, money.” Everything needs funding, and for that you need to persuade funders. It would be nice, Bason said, if he could take investors down to a beach in Portugal, show them the blooming, ruby-red kelp, and “the beauty of the plant” alone would convince them to sponsor farms. But, that’s not the world we live in. “That transition requires people like me to get into the net present value—to explain the value of the investment in money.”

After a program to install hydroelectric generators into the East River stalled (not enough funding), Bason turned to aquaculture. Now he’s a kelp expert in the business of carbon credits. Outside of the European Union, most credits are bought on “voluntary” markets, by companies wishing to tout their green credentials. As regulations requiring companies to disclose their total emissions loom, the offset industry is growing quickly. It quadrupled in value in 2020 alone, and is projected to reach up to $40 billion by the end of the decade.

Bason has as much love for seaweed as anyone. “It’s amazing,” he said on a videocall, his arms animating the waves of an underwater forest. “In Maine, I was just struck, you know: people walking on the beach with seaweed and complaining and this type of thing. This is a cure to cancer! Wake up!” He tells stories of his favorite kelp, Asparagopsis armata (“we call it ‘Aa’ for short”), in tiny individual filaments underwater, or “great red fields of it” washing ashore. “You really get to wonder how the plant figures out how to do all this,” he said.

Finding the middle ground between his own “wonder” and the boardroom talk needed to engage investors is, Bason said, “a constant struggle.” Sometimes he gets it wrong. When we first met, Bason was in the trenches of pitching Asparagopsis to cattle ranchers in the Southern Hemisphere. A natural compound in the plant, when fed to cows, miraculously reduces their methane emissions by 80%. By adding a single pellet of the chemical (extracted from the kelp) to each cow’s lunch, farmers can start to sell the methane they’ve kept from entering the atmosphere as credits to companies like Disney and Shell. Those credits, Bason said, would be counted, verified and given the seal of approval by Verra, a carbon offset verification company.

A month before that conversation, a Guardian investigation found that 90% of Verra’s rainforest credits were made-up “phantom” offsets, some doing more harm than good. It was a scandal which shook the company’s reputation and led to them replacing their entire rainforest offset scheme. When I next saw Bason, he admitted he had made a mistake “pushing” investors to trust Verra, but a mistake borne of the dynamics of business negotiations. “I was trying to simplify,” he said, “because I get ten minutes before their eyes glaze over.”

Verra is just one example of why other experts are skeptical about carbon offsetting as a whole. Russell Reed is the social conscience of Sway, a startup engineering plastic alternatives from kelp. For Reed, it’s vital that climate solutions stay integrated with communities and their green economies. Initiatives like Running Tide—which capture carbon for Shopify and Microsoft with sinking kelp buoys—risk missing the kelp for the forest. “Growing to sink is kind of silly,” said Reed, when kelp can be used in cement, plastic-alternatives, or biofuel.

“I think for people who are looking at carbon, carbon, carbon, that’s where you see this push for scale that almost immediately tends to cut communities out,” said Reed. The same cost-effective thinking is behind Marine BioEnergy’s mechanized farms, which will employ drones to harvest the kelp. “Using robots starts chipping away at all the other benefits that we see from seaweed farms that are formed by communities. It’s all about getting rid of the community component,” said Reed.

There are scientific reasons to be skeptical of industrialized kelp, too.

“Gobbling up nitrogen can become a very bad thing when you have too much seaweed and it is sucking up all the nitrogen other native species use,” said Reed. Nonetheless, he remains a firm believer in nature-based solutions. “These systems have been around a lot longer than the industrial ones which caused this headache,” he said. They just need to be developed thoughtfully and with care.

Gilman-Sevcik cannot please everyone. Bason would rather see more scale. But for another kelp project in the city, one year older, RETI does too much to monetize the plant already. “I cut that relationship off,” said Shanjana Mahmud, a volunteer growing kelp in Newtown Creek, who was last year part of an informal board advising RETI. “I wasn’t convinced by some of the things that were being claimed,” she said, particularly when it comes to carbon capture. “I’m just dubious.”

“I am anything but a kelp skeptic,” she went on. “I am a greenwashing skeptic.” With regard to RETI in particular, Mahmud wishes there was more research to back up the project. “There’s not enough critical, serious working done to vouch for these claims they’re making.” For the sea-cement, RETI are partnering with EDM, a Dutch engineering firm. “If you really want to say this is ecophilic concrete,” she said, “is what they’re doing enough or is it just a way that they’re allowing something that isn’t completely true to get funding?”

Newtown Creek Alliance planted their first crop back in 2021. In the midst of an international, corporate kelp craze, even Mahmud’s small, local project has attracted investors. “I don’t see Newtown Kelp as a product,” she says she told them, but as a way to recover the area’s ecosystem. “Enough of equating everything with capitalism,” she said. “There are people that are working in a different framework, and that’s OK. It’s more than OK, it’s time.”

Presented with this criticism, Gilman-Sevcik respectfully disagreed. Asking to make change without making money is a dead-end, he said. “It’s like telling the wolves to be vegetarian.” We live in a capitalist society whose language is money. For now, climate solutions are going to have to speak that language if they hope to work.

Kelp is a winter crop, growing from December to May, most rapidly in the final few weeks of slightly warmer water. As of late April at the RETI farm, most lines have grown well and others have failed, but most of the surprises have played out above water.

Gilman-Sevcik and the volunteers have noticed geese squatting on the pontoon on sunny days—and flocks of seagulls, careering in wide circles or bombing down into the water. It’s probably a good indication of the ecosystem the farm has created, even at its current scale.

It begs the question: what the Gowanus Bay would look like as a kelp forest, not just a farm? So Gilman-Sevcik has decided to leave some fronds in the water through summer, a more permanent “biome.” For now, the change just means more seagull droppings for the volunteers to walk through to get to the lines.

During checkups now, volunteers are no longer scraping off slipgut or retying seed lines, but carefully looking for the first signs of degradation in warmer water. When the time is right, they’ll harvest. The crop will go to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to test for diseases and heavy metals. It’ll show both how effective the kelp has been at removing pollutants from the water, and just how limited its use may be.

RETI kelp a month before harvest. Daniel Shailer

One blazing Wednesday afternoon in late April, the last time I saw Gilman-Sevcik on the barge, I asked him how he’ll remember this first, experimental year of kelp.

“We really didn’t know what we were doing,” he said. “We try a lot of things without knowing if they’re going to succeed, and oftentimes they don’t succeed at all. This has been a pretty amazing success.” RETI has already secured funding to grow the farm four times bigger next year.

The same afternoon Khalil Benedict, a 23-year-old Brooklyn local in his first few months working for RETI, was helping Gilman-Sevcik, together with Ben, a tenth grader filling out community service hours. While Gilman-Sevcik takes a call in the barge’s cabin, Benedict gives Ben advice: about school, basketball, and work. Much of the career advice is to find a job that still gives you time to play basketball.

Benedict graduated from night classes last January with his high school diploma, looking for “any type of job that was willing to hire,” he said. Here Ben listened in. “Everything except fast food. I was never putting myself in a fast food predicament. Because I know my temper.”

Benedict working at the farm one afternoon. Daniel Shailer

Applications went unanswered until an old teacher pointed Benedict to RETI’s solar training program, which took him on and hired him this year. “I feel like what they gave me opened the door,” he said. “Now this is me. I see why I’m here; I see how I got here; I see how my life is the way it is. I see what I can do to give my part to the earth.”

When people ask Gilman-Sevcik whether work like kelp farming actually moves the needle, whether it’s not just another Brooklynite performance of advocacy—he answers with stories like Benedict’s. “We have multiple people in our training programs who are just getting out of jail, are in jail,” said Gilman-Sevcik, “and have never thought about or heard about anything to do with renewable energy, or environmentalism.” Benedict himself arrived at the barge that day from court: a preliminary hearing for an arrest while he was unemployed.

For Gilman-Sevcik, training the next generation is another kind of climate adaptation. “This is going to be their burden more than anybody else’s. So the idea that you’re getting a generation of people from this community that will be the most affected to be thinking and knowing and learning and working—adapting to climate?” He smiled and shrugged. Enough said.

“How are we going to distribute stewardship, if we don’t allow people to have some kind of engagement in it? Bringing people down here and letting them mess around with kelp is going to increase their enthusiasm for it. If they can actually have a job doing it? All the better! So it’s not for people to make money and get rich, it’s for people. People need to live and they need to earn money to live.”

While working that afternoon, Gilman-Sevcik slipped away for calls, argued the greatest basketball player alive with Benedict, and told Ben (and me) to put on sunscreen. In that time, two local teachers visited and the owner of a prop shop for movies introduced himself to donate some rope. Coincidences like that happen every day on the farm, Gilman-Sevcik said, and it’s convinced him something is going right.

“That just keeps happening. Literally, we’re like, ‘Oh, my God, where are we going to get rope?’ This guy walks down. It’s like, ‘Oh, rope?’” he said. “When I talk about Gaia, I’m not joking, I am a person of faith at this point. I believe that we can align ourselves with this organism of Earth. And when we align ourselves with the organism that we are a part of, then things happen.”

Gilman-Sevcik checking kelp. Daniel Shailer

A small kelp farm in Gowanus Bay will not save the world. Until tests reveal how much pollution the fronds absorbed, it’s not even clear it can save the Gowanus. But to Gilman-Sevcik, the world doesn’t need saving from the “maverick species” setting it on fire. We need it to save us.

“We will not solve climate change; we will only adapt to climate change,” he said. “We will mitigate the damage; we will slow the damage—but the damage is done and the earth will heal at its own pace. The quicker we stop hurting it as much, the quicker it’s going to be able to recuperate.” ◊

Leave a comment