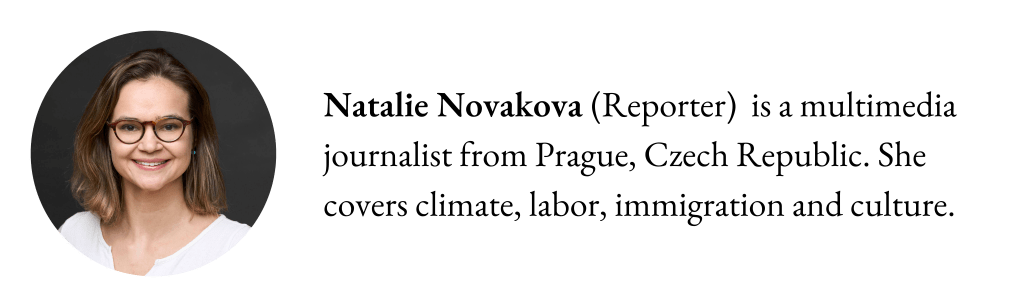

Snow and his former student Laure Raymond stand next to three bee hives, which are part of the apiary of Snow Lab. Natalie Novakova

As wide scale die-offs threaten bee populations around the world, one scientist tries to solve a climate mystery.

Natalie Novakova

Every March, on a rooftop at Barnard College, in the heart of Manhattan, three beehives begin to buzz with life. Each year, thousands of bees prepare to get working for the season, and so does the Snow Lab, led by Professor Jonathan Snow and his student team.

Honeybees are crucial pollinators, supporting many different crops across the United States and the world. In recent decades, bees have been dying at much faster rates than previously. The exact reasons for this die-off remain a mystery. Snow is working on changing that.

“If honeybees continue to have problems, or maybe even if their diets worsen over the next few years, there will be increased pressure on the agricultural system,” Snow says. He worries about what will happen if the trend continues.

Snow first began studying bees as a hobby. He had done his Ph.D. and post-

doctoral work on mammals: their signal transduction, regulation of gene expression, and stress responses in blood development. Towards the end of his postdoctoral study, he decided to focus on ecologically related problems in food production and agriculture.

A much smaller organism soon captured his attention: bees. After attending a beekeeping course in New York, Snow found their biology captivating. “I just started thinking about different organisms and different systems,” he said, “and I just happened to take a beekeeping class.” There was a natural human interest in bees. “I think since humans have been human we’ve been

interested in bees,” Snow said, “because they sort of remind us of ourselves a little bit.” Bees were an ideal organism for him to study because they were having a health crisis at the time. Large scale die-offs, caused by what is known as colony collapse disorder, resulted in many worker bees disappearing. “By the time I was thinking about what to study, it was like 2008, that”—the large-scale die-off—“was really on people’s minds, like how to figure out what was going on with bees.”

Snow had no prior knowledge of honey bees before enrolling in the beekeeping course. He went one day a week for five consecutive weeks, learning about the basic biology of bees and basic beekeeping techniques—nothing in-depth. But after completing the course, he started beekeeping on his own. He purchased two colonies during the first year and kept them at his home. “I didn’t think at the time that was going to be what I ended up studying,” he said.

Jonathan Snow’s desk in his lab at Barnard College.

In 2009, Snow started researching cellular stress responses and the infectious diseases of honey bees, which are a keystone species, meaning they have a critical role in maintaining the structure of the whole ecosystem. Coming from a biomedical background meant that Snow’s approach to studying bees was quite different compared to entomologists and ecologists studying bees. “Honeybees are really interesting because they have a really impressive ability to regulate the temperature of their colonies,” says Snow. “But still, the extreme temperatures associated with climate change can be dangerous for them.”

He started researching bees at Williams College in Massachusetts. After two years, he was able to publish a paper, mentor undergraduate students, and build on his teaching experience. In 2012, he was offered a full-time position at Barnard, along with funding (and space) for a small rooftop lab to study bees.

Snow’s first research experiments looked at immune function. “I realized that we didn’t know enough about a lot of the basics,” he said. He and his team quickly shifted the research focus to stressors affecting bee health. Over the next couple of years, the lab was able to refine their research questions and reflect more on what the most important unknowns in the field were. However, the main focus remained the same: honey bees and their health. Next, he started looking at immune responses to stress.

More recently, one such stressor has particularly stood out in his research: climate change. “In the ten years I’ve been studying bees, climate change has just become a lot more urgent,” says Snow. Part of this is the result of increased public awareness about the issue, but also more understanding of how immune stressors intersect and work together to affect honey bee populations.

Bees are also under pressure because the natural world is changing around them. One of Snow’s old friends and colleagues, Noah Wilson-Rich, a bee researcher and author of The Bee: A Natural History, explains that due to climate change “we’re starting to see a mismatch in the timing of blooms, between the flowers that are available to give bees good nutrition and the bees that are then out there burning through their food and essentially dying off because they’re starving.” Bees leave the hive to search for food because the weather seems to indicate that food will be out there, and they cannot find it. It’s only February. They fly further and further because food is just not close enough.

“As the weather in the world changes and the seasons change, other organisms start to change their biology and behave differently,” says Snow. “Understanding honey bees will help us to understand how these stressors and climate change are going to impact these other species.”

Honey bees and early hominids have coexisted for at least two and a half million years. In the Old World, Homo sapiens were confined to at least one species of honey bee (Apis). The alternating periods of extreme climate conditions such as ice ages and warm periods influenced sea level changes and ultimately encouraged the migration of people into different regions of the world. At this time bees were used mainly for honey production as well as wax collection, which would later be used in parts of the world for gold casting.

The earliest known representations of nests and bees appeared in rock art. Beeswax itself was used as a painting medium in Palaeolithic rock art in Spain and France dating to around 15,000 and 13,500 BC. Most rock paintings depicted honey hunters at wild honey bee nests. To keep track of rock art related to bees a register was set up by Eva Crane, one of the greatest writers on bees in the twentieth century. In 1986, the list included 118 likely sites in 18 countries, including Spain, KwaZulu Natal, Zimbabwe, India, Bhutan, and Australia. In India, the bees were represented by dots or blobs, whereas in Spain paintings indicated body shape.

Scientists have suggested various reasons for human interest in honey and bees. Many researchers believe that primates’ general consumption of fruit was the main cause for humans’ great love for sweetness in food. Therefore early humans sought honey nests not only for the beeswax, used to glue together arrows, spears, and pottery, but also as a sweetener in their diet, as it was easier to find compared to other sources of sugar.

It was the Ancient Egyptians, circa 3,500 BC, who first domesticated hives and mastered honey production on a large scale, leading honey to be used by all classes of society.

Now in the world, there are currently over 20,000 species of bees, 4,000 of which are native to the United States, about four times the number of bird species. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, around 10% of native bees in the U.S. are yet to be named and described.

It was once thought that the first honey bees came to the United States with early European colonists in 1622, however a 14-million-year-old fossil of an extinct honey bee (discovered in west-central Nevada) suggests that honey bees were in North America a long time before that. During World War II, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) committed to increasing honey and beeswax production by 20% as a response to sugar being in short supply. Apart from honey, beeswax was also in dire need. It had 350 uses in wartime military operations and industries from coating airplanes, shells, and drills, to waterproofing tents, tapes, and varnishes. This brought an emphasis on honey marketing and production. Hobbyist beekeepers were replaced by scientists trained for the USDA.

The first person to study bees scientifically was the Nobel Prize-winning German-Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch, who devoted his life to the study of honeybees’ behavior and their sensory perceptions. In his book, The Dancing Bees, he described how these pollinators communicate the distance and direction of food through figure-eight “waggle” dances, suggesting that bees are capable of distinguishing various blossoming plants by their scent.

According to researchers, at least 90 commercially grown crops depend on bee pollination. Why are bees such successful pollinators? It’s their sight! Von Frisch discovered that bees can see color, and have broader color vision than other pollinators. Bees are attracted to the vibrant petals of flowers, where the nectar is located. Unlike humans, bees can see ultraviolet light, which enables them to spot nectar patterns on the petals of sunflowers, primroses, pansies, and other nectar rich blossoms. Bees can also see color much faster–five times faster than humans, to be precise.

Each honey bee colony counts somewhere between 10,000 to 60,000 bees. In the United States by 2021, there were approximately 2.7 million domesticated honey bee colonies.

Honey bees have an average lifespan of up to five years. They produce honey and beeswax. In the hive, they are social and cooperative. Unlike honey bees, native bees, such as North American bumblebees, are mostly solitary instead of nesting as a hive.

Habitat loss and increased use of pesticides (driven by commodity crop production) mean that the U.S. native bee population is on a steady decline, with at least 23% lost between 2008 and 2013. When it comes to honey bees, the Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that the number of beehives declined by 40% between 1970 and 2019. More recent data from BeeInformed suggest that only between 2020-2021 an estimated 32.2% of managed bee colonies were lost in the US, an increase of 9.6% over the previous winter loss. The causes are varied and include Varroa mites, pesticide use, habitat loss, and most recently climate change.

Now scientists and academics are trying to help bees survive extreme weather conditions and other obstacles they might encounter. A study published last year in Nature suggested that climate change, along with agricultural expansion and over-exploitation, can play a fundamental role in honey bee colony loss as well as affecting the ability of honey bees to forage, thermoregulate during winter, and breed during spring.

Jonathan Snow is a sporty and cheerful man. It’s a bit chilly on the day we meet, in mid-March, so to protect his ears he wears a Norwegian-pattern winter hat. He walks swiftly toward the historical, Colonial-inspired, four-story Milbank Hall, which now hosts his bee hives on its roof.

Laure Raymond, a former student and alumna of the Snow Lab, follows him closely. She is wearing white protective gear atop a gray hoodie. Raymond now works as a nurse in Brooklyn, but she likes to look in on Snow and the bees when she has a chance. Today she is visiting the college to give a talk. A black netted protective hat hangs off her neck.

Snow comes to the rooftop to inspect his apiary anytime the temperature goes above 50°F. He recently moved his three hives from Barnard Hall to Milbank Hall due to construction. Snow explains that before moving the hives, they had four. Now, in front of him, only three hives remain. The cold winter killed one of his colonies. Snow says it’s nothing unusual, but he admits that fluctuating temperatures are putting pressure on his bees.

“I think understanding the impacts of climate change on different organisms is important, both in trying to understand how it’s going to impact those organisms, but also how it’s going to impact all of the interconnected organisms in our ecosystem,” says Snow.

Snow conducts most of this research during the summer months. He says it’s hard for him to describe the process because one has to come and see it with one’s own eyes. This summer, he and his team will be focusing on how thermal stress is related to aging. “We’re looking at the microbiome and thermal stress,” he says.

Between April and October, the team extracts bees from the hives by collecting them from the landing board of genetically diverse colonies. They put them in specially designed transparent cages with air holes, so the bees can continue breathing. Then they place them in a chamber and expose them to different temperatures for a certain amount of time. During the experiment to imitate heat shock, the scientists keep the bees for four hours in cages at 95 to 113°F. They also keep one bee population at a normal temperature. They then take the bees back out, place them under cold anesthesia and remove their mid-gut and head, thorax, and abdominal wall tissue. Next, they would usually extract RNA and then convert that to something called cDNA, which the scientists could use to see which genes are turned on and off in response to the thermal stress.

Snow shows a cage he designed for extracting bees on a tour of the Snow Lab in Barnard College.

In 2021, Snow and his students published a paper, “Thermal stress induces tissue damage and a broad shift in regenerative signaling pathways in the honey bee digestive tract,” in the Journal of Experimental Biology. The paper hypothesized that honey bees can withstand extreme temperatures due to their heat shock response system at cellular level. However, the study highlights that little is known about how and whether extreme heat causes tissue damage response in this key pollinating species.

Snow gives an example of one of his students this year. “There is a student in my lab right now who is using some RNA samples that we generated last summer. She’s looking at gene expression and those from a different kind of bee, actually an alfalfa leafcutter bee.” This summer, the student will be going to get bees from outside and put them into the cages. She will be doing this for the next five months. The students with Snow will be conducting new experiments every week for this period.

Many of Snow’s papers begin with the same refrain: bees are dying more quickly than ever before, and the reasons “are poorly described.” There are “stressors” such as pesticides, pathogens, and microbes–but also, importantly, “a myriad of environmental changes attributed to climate change.” These include the fact that the natural world around bees is rapidly changing, and the flowers they rely on for nutrition are either not blooming or blooming at a time the bees do not expect. Snow and his colleagues are not yet at the point of proposing solutions to this problem. They are still trying to figure out what exactly is happening–at the cellular level, at the level of the colony, and at the level of the ecosystem.

Snow walked me around his lab and talked to me about bees for more than an hour. He showed me the fridges where they keep the different chemicals, the bee larvae that he orders online, and the boxes where they keep the hives during the winter. He was justly proud of the lab he had built over the past decade. Eventually, it was time for Raymond, his former student, to go give her a talk, and it was time for me to head home. We walked out together. Snow stayed behind, to tend to his bees.

Bees have been on the minds of legislators and researchers across the country. Pollinators support nearly 35% of global crop production and bees are considered one of the most important pollinators in temperate climates. According to studies, honey bees are responsible for pollinating more than $15 billion in crops annually in the United States. On the other hand, native bees, although individually vital pollinators, are responsible for only a fifth of the crop value annually within the United States.

Officials, such as State Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Basil Seggos, are open about linking the poor health of honey bees and climate change.

New York State (NYS) alone is home to more than 80,000 bee colonies, which pollinate more than $300 million worth of crops across the state annually.

To ensure that bees stay alive and are healthy, and to address the state-wide decline in pollinators, NYS has implemented several initiatives including; NYS Pollinator Protection Plan and The NYS Honey Bee Health Improvement Program, alongside initiatives to support beekeepers and improve their knowledge such as The Urban Beekeeping Initiative, The NY Bee Wellness Workshops, and The NY Beekeeper Tech Team.

The NYS Pollinator Protection Plan, created in coordination with the Pollinator Task Force group, and introduced in 2015 by Governor Andrew Cuomo, aims to reduce harmful pesticide use and promote habitat conservation by adding $500 million in pollination services annually. The program specifically focuses on two groups of pollinators: wild pollinators (bumble bees, butterflies, and beetles) and managed honey bees. The current form of the program focuses on the four most important areas: development of voluntary best management practices, habitat enhancement efforts, research and monitoring, and development of outreach public education programs.

More recently NYS announced an update on its Pollinator Protection Plan by recommending the creation of a Cooperative Honey Bee Health Improvement Plan to increase the number of pollinator-friendly habitats and to continue research about major stressors for honey bees, including climate change.

Dr. Gloria DeGrandi-Hoffman, research leader at the Carl Hayden Bee Research Center in Tucson, Arizona, leads a grand challenge project that addresses climate change and its effects on all pollinators including non-native species. She says the way pollinators are affected by climate change is two-fold: immediate effects and more subtle effects.

“You just can’t miss it. It’s a sledgehammer,” she says about the direct immediate impact of climate on honey bees.

“We’re in an unprecedented time of megadrought and this has greatly impacted honey bees because the lack of rainfall means that we have fewer flowers and flowering plants available,” says Dr. Diane Cox-Foster, research leader of the USDA Cross Pollinating Insect Research Unit in Logan, Utah.

Cox-Foster adds that the researchers still lack the knowledge of how honey bees deal with temperature stress. Some bees go into hibernation, some die, some, especially in the American southwest, can overwinter in hedges, and others come around at different points of the season because plants are not available. “We don’t know what the extent of that is and how resilient they are,” she says.

The second way in which pollinators are affected by climate change, according to DeGrandi-Hoffman, are warmer fall temperatures that cause bees to fly later in the year. She explains that as the bees fly, they age, and when they finally get into a cluster (the main brood area of the hive) during winter, their age might mean that they are unable to build into large colonies in the spring because they are not strong enough.

According to Wilson-Rich, we are seeing a kind of broken agricultural system all across the world, not only in the US. For example in Canada, where American bees are illegal, they have to fly bees in from New Zealand.

This unsustainable practice, introduced by Canada in 1987 to prevent the spread of Varroa mites, in turn contributes to more carbon emissions and climate change. “The ways that humans go about fixing this and addressing the negative impacts of climate change can be quite silly,” Wilson-Rich adds.

On the national level, other solutions have emerged to address the impacts of climate change on honey bees. “Some of the larger beekeepers where it’s a major business for them, climate change is on their mind and critical,” says Cox-Foster.

One of the smaller-scale solutions is purchasing a cold storage unit that enables air quality and CO2 monitoring. These refrigerator units are not easy to build and are a large investment.

Meanwhile, researchers like DeGrandi-Hoffman study the nutritional composition of pollen to see how they match up with what the honey bee colony needs.

Having conducted vast research himself, Wilson-Rich says that one way of improving bee health in the long term and on a larger scale is through the foraging habitat. “I’ve been consulting with the U.S. federal government on how to improve what we’re planting. It helps us understand the timing of the planting and what was lost and what can be gained over time by having this conversation,” he says, referring to habitat loss happening due to climate change and greater urbanization.

To mitigate other large scale climate impacts on honey bee populations, it will also be important to reduce pesticide use, closely monitor weather conditions, and provide sufficient clean water and heat shelter near hives.

During the year Snow has a lot on his plate. He is currently teaching “Introduction to Cell and Molecular Biology” to more than 250 students each week. But bees remain his passion.

When the summer finally comes, he cannot wait to get back to his honey bees on the rooftop of Barnard. He gets excited and is eager to share his interest with like-minded students, who are open to learning more about this essential insect. With a thrill in his voice, he talks about the plan for the summer and how he and his students will conduct the research. Meanwhile, bracing for the seasons to come, he plans to order more bees for a fourth hive to replace the one that he lost this winter.

“So we actually went and got some package bees a few weeks ago and got new colonies going,” he said. Now, Snow is waiting for those new colonies to take off.

Technical equipment in the Snow Lab.

Leave a comment