J.J.’s father lost his life in the underpass at Passaic and Van Houten in Passaic, New Jersey on the night of Hurricane Ida. Lue Palmer

A survivor of Hurricane Ida is finally returning to his old life. The journey from the original trauma has been a long one.

Lue Palmer

Author’s note: the main character’s name has been withheld for his safety.

The sky was dark on September 1, 2021, as J.J. drove toward home, his mother in the passenger seat beside him, and his father strapped in the back. It had been a good summer—at the age of 25, J.J. had landed the best DJ spot of his career, hosting a club night in Passaic, New Jersey, that was packed wall to wall every weekend. During the week, he worked in New York City, repairing air conditioning systems. He had a new car, a black BMW with purple interior tread lights. He had found a supportive living apartment for his parents, and they planned to move there the following week.

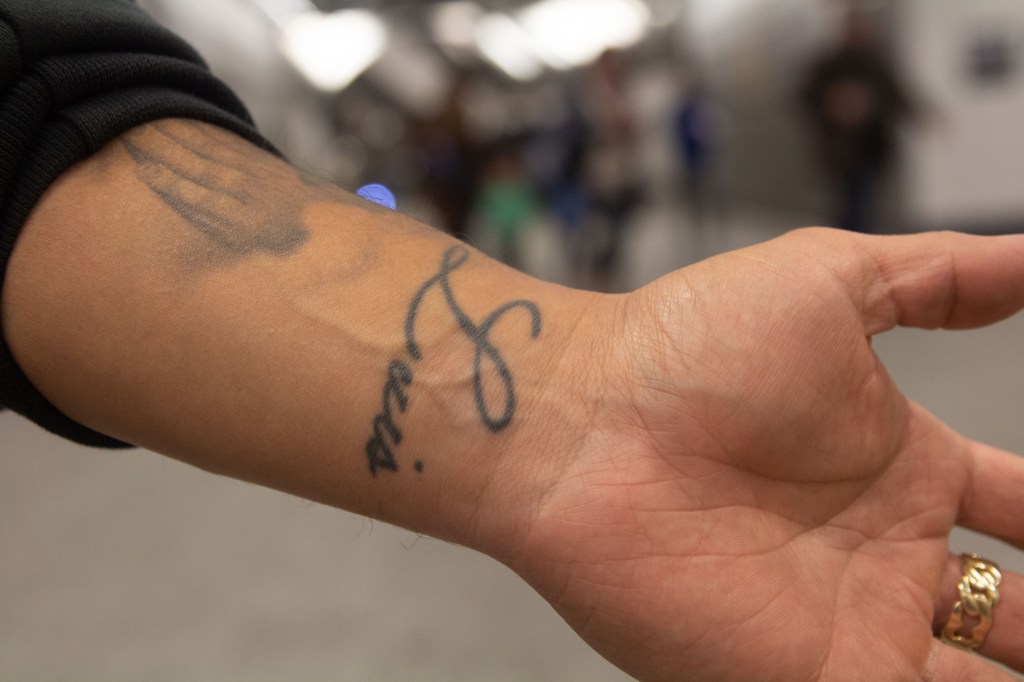

Though he was the youngest son, J.J. was used to taking care of his parents, especially his father, who had suffered a stroke many years before. The stroke left him unable to lift his right arm fully and his memory fading. J.J. had tattooed his father’s name across his left wrist.

On this night rain was battering the car as they approached the underpass at Van Houten and Passaic, near the train station, just four minutes from home. The underpass ran beneath the train tracks, forming a small valley. Water was now running into it from both sides. A river had overtaken the road.

At first J.J.’s tires were firmly on the pavement, and then, very suddenly, they weren’t. “Imagine driving, and it just starts to float,” he said.

Suddenly, the engine cut. J.J. knew this meant that water had soaked under the hood. He took out his phone and called the police. Suction from the storm drain was pulling the car into the underpass. Inside the vehicle, water was rising around their feet up to their thighs, against the purple tread lights. The car began to sink.

It took only three minutes to hear the sirens of the fire trucks from the nearby station. J.J. could see the lights beyond the water, but the emergency services were unable to reach him and his parents. They would have to get out of the car. But the engine was off, and the power windows would not go down. His father was still strapped in the backseat. J.J. tried to break the window, hitting it repeatedly, but could not make any impact. His mother was struggling with the window on her side. With the very last of the car’s battery, she managed to roll it down a small crack—a space about five inches wide. J.J. forced himself between the space, so narrow it bruised his body on the way out. Free of the car, he turned to retrieve his parents and saw the vehicle had sunk under the surface of the water.

His mother was struggling out from the window, but she could not swim. His father was now completely submerged, and strapped in the backseat, unable to free himself. J.J. made a choice. Holding his mother above the water, he swam with her toward the edge of the underpass. He struggled with her against the current, towards the stairs that led up to the train station. When they had reached solid ground, J.J. collapsed from exhaustion.

It was 2 a.m. the following morning when the scuba team was able to go under and retrieve his father’s body.

J.J. and his family are among the thousands who were affected by the floods of Hurricane Ida. Like the victims of Hurricane Sandy in 2012, they will have to manage the mental health impacts long after streets have been repaired and people have returned to their homes.

I first met J.J. in person at a bubble tea restaurant in Midtown Manhattan. We’d spoken twice on the phone about what he and his parents had endured on September 1, 2021. During those weeks, I was calling families and going door to door in areas of New York and New Jersey that were intensely impacted by Hurricane Ida, like Passaic County. Down the street from the underpass where J.J.’s father lost his life, neighbors also remembered a young woman and man who were swept away in the storm and found a week later. Some families said simply of the hurricane: “We think about it every time it rains.” One woman in Woodside, Queens, began to cry at the first mention of Ida, as she stood in her front yard sweeping debris from the stoop. It was clear that the impacts of the storm had not yet been resolved, a year and a half later, and that for many it was still a source of pain.

J.J. stands on a subway platform on his way home from work in Manhattan, a year and half after Hurricane Ida. New York City, April 2023. Lue Palmer

Modern American disaster relief began to take shape in the 1970s, partially in response to the devastation of Hurricane Agnes. Though not widely spoken of today, for the people of New York and Pennsylvania, Agnes was an unforgettable event. The storm hit the region in late June of 1972 and dredged the dead from the cemeteries as the Susquehanna River overflowed.

“Ingrained in their psyche are the sounds of sirens, the smell of mud, and the visions of dead bodies floating down the streets,” wrote Bryan Glahn, author of Hurricane Agnes in the Wyoming Valley. “Their lives will forever be defined in two parts,” Glahn wrote, “before ‘the flood,’ and after.”

At the time, Hurricane Agnes was the costliest storm in United States history. Agnes was followed a few years later by a swath of devastating tornadoes across the country that resulted in “six Federal disaster declarations,” according to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and “as a result, the Federal government passed the Disaster Relief Act of 1974, which consolidated many changes that had been initiated in the period following Hurricane Agnes.”

Two years after the hurricane and facing impeachment, President Richard Nixon signed an amendment to the Disaster Relief Act. Among other supports for the recovery of communities, the amendment would allow for “crisis counseling,” for victims of disasters. This represented a significant acknowledgment of not just the physical damage of events like hurricanes and tornadoes, but that the risk to psychological health was so great, it warranted a national response.

In 1988, the Disaster Relief Act was refined and amended. While sitting in the White House Rose Garden on August 11, 1988, President Ronald Reagan spoke to a congregation of Illinois farmers, who had been plagued by a severe drought that year. “The bill that I’m about to sign,” he said, “represents the largest disaster-relief measure in history. The bill expresses a distinctly American tradition: that of lending a helping hand when misfortune strikes.” He spoke mainly on recovering material losses from similar disasters, and included Reaganesque caveats about fiscal responsibility. Nevertheless, it signified an important step forward in creating a clear process for states to provide psychological services in the wake of disasters.

Also renamed the Stafford Act in 1988, it “defined emergency management as a joint responsibility of Federal and local governments,” according to the New Jersey Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Disaster, and Terrorism Branch. Most significantly, it “required states to have a plan for the mental aspects of a disaster.”

This support would be administered by FEMA under the Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program, a short-term funding program granted to states for “community-based outreach, counseling, and other mental health services,” according to Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration which would work with FEMA to administer the program. Together, they would coordinate the training of mental health professionals in the local community and at the state level.

The Stafford Act established two tiers of the grant program covering mental health: the immediate services program providing support for up to sixty days after the disaster, and the regular services program. In order to access these services, each individual state would need to apply for the programs within two weeks after the President were to make a declaration of a major disaster, according to FEMA’s guide for the application process.

The Stafford Act was amended again in the years 2000, 2006, and once more in 2018 under the Disaster Recovery Reform Act, which stated a strategic goal to simplify FEMA’s processes, “in order to be able to adapt to the public and the government’s priorities by streamlining the disaster survivor and grantee experience,” according to the Reform Act report from 2019. However, none of the amendments specified an expansion or extension to the crisis counseling program.

The Stafford Act was designed to provide support for the kind of events that have become increasingly commonplace over the last thirty-five years: hurricanes, tornados, tsunamis, mudslides, droughts, and fires—climate change consequences that have redefined the lives of people coping even several years after, and beyond the one year period outlined for support.

Although federal support through FEMA allows for crisis counseling for up to a year after a hurricane, experts warn that mental health and trauma recovery can take much longer. Furthermore, the Crisis Counseling and Training Assistance Program requires each state to apply separately, leaving room for inconsistencies in disaster mental health support across the country.

The day after Hurricane Ida, J.J. took a leave from both of his jobs. He felt numb. He gave up on moving his mother to an assisted living apartment, and she came to live with him permanently. The weight of what they had experienced was too much. In the months after the storm, they received a small amount of funding from FEMA to cover the loss of J.J.’s car, but he wasn’t aware of any funding for mental health support. They started an online fundraiser to pay for his father’s funeral.

J.J. gave up his DJ gig, in an industry where being away can cost a person their position and notoriety. He had spent years learning his craft—since he was 15 and his parents had taken him to a youth music program. At first, he DJed family parties and gatherings for aunts, uncles, and cousins. In a few years, he established himself in the club scene in New Jersey. But after the hurricane, he stayed home. He did not want to go out in public.

The second time J.J. and I met in person, we sat inside a pizzeria on the upper east side of Manhattan. I had come to ask him more details about the night of the flood, and losing his father but I was worried about upsetting him. I paused frequently, to see if he needed me to change my line of questioning.

“Can I continue?” I asked.

“I did a lot of therapy, bro,” he said. “Like, it’s good, trust me.”

I had wondered what made J.J. different. He was able to retell his story with such detail and clarity, when so many of the families I spoke with seemed hardly able to think of the night of the hurricane, without crying or showing signs of distress.

J.J. told me that a close friend had encouraged him to see a counselor in the weeks after the storm, and referred him to a therapist who was willing to give free sessions as a favor. J.J. agreed to go, but said it was difficult at first. The counselor had him “relive the event,” by talking through everything repeatedly, and bringing back memories of the night in the underpass.

“In the beginning, I thought it was hard. Hard therapy. But now, I understand,” he said. “That’s the worst thing that anybody can do, just be quiet and not talk about anything. You take your feelings and you progress. You work with it.”

J.J. spoke to his mother about therapy sessions and tried to convince her to go. Therapy was not something she had grown up with in Ecuador, but she was willing to try. She even sat in on a session with J.J.’s counselor to see the process for herself, though she wasn’t able to understand much because the therapist couldn’t speak Spanish. J.J. thought she would benefit from her own sessions, and they tried to find her a Spanish-speaking counselor close to home. In the end, they weren’t able to find a good fit, and she went without.

Two months after the night of the hurricane, J.J. returned to work at his job repairing air conditioning units. He still had not returned to DJing parties and the work he loved most before the storm. Even with the support of therapy, he struggled to adjust. He taught himself how to break open a window with a small wrench that he attached to his belt. He bought a glass breaker and a seatbelt cutter. He visited an old junkyard to practice breaking windows to make sure the glass breaker really worked. “If I would’ve used that that day, I could have saved myself another minute or two to figure it out,” he said. It was six months before J.J. returned to DJing. He found he had lost ground in the industry.

J.J. continued to see his counselor for a year. “I went from getting choked up about it or crying about it to where I’m at today,” he said. “And obviously, when time progresses, you get better at it, but you don’t ever want to start going downhill because then you lose that self-esteem and you start hiding. Then comes depression and all that shit. You don’t want that.”

Though he believes therapy helped him a great deal in his recovery, a year and half later, J.J still will not drive through the underpass. He avoids going outside when it’s raining, and if he has to go to work, he drives very slowly, thinking about what could go wrong in such a short time.

J.J. holds his glass breaker in his hand. Lue Palmer

“I’m not fully recovered,” he said. “That feeling is always going to be there, but you just have to combat that. Just keep your head right.

“Getting help early made it so long-term I could be okay.”

Studies have shown that receiving mental health support in the immediate aftermath of a disaster can be crucial to a person’s long-term wellness. Dr. Jennifer Runkle is an environmental epidemiologist at the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies at North Carolina State University. Her team, co-led by Dr. Maggie Sugg, has studied the mental health response to the 2020 California wildfires, and to Hurricanes Florence, Ida, Harvey, Laura, and others. They found a significant increase in “thoughts of suicide, stress, anxiety, and bereavement,” in the months after September 1, 2021, when families were beginning a long road to recovery from Hurricane Ida.

Dr. Runkle’s work describes the first four months after a hurricane as a “honeymoon period,” when resources are more plentiful, community support is more active, and there is a focus on rebuilding and recovery. There may be a greater sense of sharing a collective burden, and outpourings of national support. “And then what happens is disaster resources dry up and there’s this transition to the more severe mental health outcomes that we see,” said Dr. Runkle. “We start to see this turn around the fifth, sixth, seventh month where you see an increase in Post-Traumatic and these other adverse mental health outcomes.” During this period, people begin to deal with the psychological aftermath of losing loved ones, their homes, or the widespread effect the hurricane has had on the health of their neighbors and friends.

Dr. Irwin Redlener is a Senior Research Scholar and the founding Director of Columbia Climate School’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness. His study on the mental health and wellness of children five years after Hurricane Katrina illuminated a worrying trend of long-term mental illness and emotional disturbance in the generation impacted by the storm. His research also noted that they were largely unable to get access to mental health services.

Although Hurricane Katrina remains the costliest hurricane in United States history, the country has seen several devastating hurricanes in the 18 years since, at an increasing frequency that will only gain momentum over the next generation, raising the likelihood that a person will be exposed multiple times over their life to the psychological damage of a natural disaster. Over his career, Dr. Redlener has argued for a need to shift national thinking on what it means to recover from a climate crisis.

“When we talk about recovery, what is really mostly talked about is rebuilding infrastructure, physical communities, built environments, and so on,” he said. “And that’s part of it, but it’s by no means all of it.” There are a number of mental health support services available to victims of Hurricanes, including grants from FEMA’s crisis counseling support services which are available immediately after a Hurricane and for up to a year afterwards. However, though infrastructure repairs can also take anywhere from six months to two years depending on the damage, the resources, and the funding afforded to the community, it is much more difficult to place a timeline on mental health recovery.

“There’s no time limit to the duration of the impact psychologically for disasters,” said Redlener. “Eventually most people will recover, some way or another, but if it takes you two years or three years to recover with or without mental health support, you may have lost so much ground, so much self-esteem, so much sense of ambition to keep going on with your life.”

Though there may be a set timeline to apply for support, people in recovery, even several years after the devastation of a natural disaster, are left to cope in whatever ways are available to them. Studies have found increases in addiction from hurricane exposure, especially when that exposure is personal or severe. Those with fewer resources are also less likely to receive mental health support after a crisis. A person’s access to mental health support may vary greatly depending on their own family structure, the financial resources of their community, and the response of non-governmental organizations, and churches.

“Things are left to random acts of support and it’s hard to necessarily identify what that support is,” Redlener said. “We don’t have a consistent way that we handle things, that’s uniform throughout the country.”

Redlener stresses a need, not just for a coordinated, national response to mental health recovery, but also for the training of community members and clergy in addition to mental health professionals on how to support their neighbors and understand the challenges of long-term mental health recovery. Services like Crisis Textline have partnered with researchers such as Runkle’s team at the North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies, beginning in 2016.

“We’ve been working with the service to see: could we send out extra support in the weeks and months following these disasters,” said Runkle. Her team is looking at developing text-based campaigns to let young people know that the service is available, “as a safety net during the recovery period.” They are seeking additional National Institutes of Health funding for this, and have had a greater response from populations like LGBTQ+, Black, Hispanic and Native American youth. Crisis Text Line is also available in Spanish as of October 15, 2021. Though innovation is taking place, long-term advocates and researchers are still concerned.

“This is an ongoing, chronic problem: our general inability to understand recovery. And this has been the case for a very long time.” said Redlener. “I am worried. We’re going to have more events and not much more ability to handle the mental health aspects unfortunately.”

On a Friday night this spring, a year and a half after the hurricane, J.J. was DJing at a club in Fort Lee, in a high-ceilinged, red room outfitted with circling lights that cut through the smoke from the fog machine. Though his reentry had been difficult, he felt like he was finally back in position.

The club was largely empty at 11:30 p.m. A few people sat at the long, colorful bar, looking at their phones or else yelling over the music into each other’s faces. A few other people were sprinkled throughout the club—a man in a large, black cowboy hat sat alone at the far end of the bar; a couple at a high table faced each other; another sat in the corner sharing a hookah. Two women in tight, tiny shorts walked back and forth across the room under the red and green lights, toward the event organizer sitting near the gaping door, his braids hanging across his face.

As midnight approached, J.J. stepped towards the booth and took out his laptop. In front of him was a large DJ control station with a vast array of colorful buttons. He began to take out his equipment, moving wires, as he and the first DJ prepared to make the transition. Suddenly, the event host was busy at the door. A number of people were congregating at the entrance, becoming restless as they waited to pay cover and go inside. First, a group of young men, and then women in crop tanks and bathing suit tops, walked into the club toward the VIP corner.

The music stopped. The connection had been dropped as the DJs switched out their equipment. The dead air filled the club for a moment as the spinning lights continued to rotate through the artificial fog in the near silence. The room was tight, groans bubbling from the bar and corners of the room. And then J.J.’s music swelled outward, on a deeper and grittier beat than the set before. The crowd at the door came inside to Latin trap, afrobeat classics, and hip-hop throwbacks. J.J. stood above the crowd, his hands moving deftly over the equipment, singing along and calling shoutouts into the microphone.

All around, the club was filling with people under the green and pink light. Young men in gold chains, and women in long braids, or laid down styles, applied lip gloss, danced, twerked, and sang in each other’s faces as they laughed. A waitress brought out a bottle with a flare shooting out of it and the people cheered for her as she moved across the dancefloor to VIP.

J.J. commanded the room calmly, a look of confidence on his face. The red light fell over him where he worked across the control board. He smiled as he leaned over his equipment, his keychain and wrench secured tightly at his hip. ◊

J.J. has his father’s name tattooed across his wrist. Lue Palmer

Leave a comment